William Blake discussion at the University Press Bookstore in Berkeley, November 2019

Exploring the Classics

Chronicle of a Book Group

Over the last couple decades I’ve led or taken part in a number of book discussion groups. Some have dealt with radical texts, others have explored various literary works. These two types of groups involve rather different aims and attitudes, but I think they also complement each other. The first type focuses on radical tactics and strategy — how we might better understand and transform the absurd socio-economic system in which we find ourselves. The second is more leisurely and open-ended — exploring imaginative works that enliven and potentially illuminate our lives in general.

But precisely because they deal with the basic archetypes of human experience, these latter works often turn out to be surprisingly relevant to present-day issues. They continue to engage us because they address the perennial life issues that we all face in one way or another. They give us a better sense of the varieties and potentialities of human experience, from the sublime to the ridiculous. They raise difficult questions rather than offering easy answers. And contrary to popular misconception, they are also among the most entertaining books ever written; if they weren’t, they wouldn’t have continued to be eagerly read and reread by countless people over the centuries.

Since January 2016 I’ve led a group called “Exploring the Classics.” Until March 2020 it was hosted by University Press Bookstore in Berkeley. Following a short hiatus at the beginning of the pandemic, the group resumed in July 2020 via Zoom, and will probably continue that way indefinitely. Although we miss the previous in-person conviviality, we would miss even more the many new friends in other parts of the country and even in other countries whose participation Zoom has made possible.

From September 2023 to December 2024 I also led another Zoom group (alternating Sundays with the Classics group) called “Exploring the Situationists.” Because of the different nature of the material and the larger number of interested people around the world, I recorded all the sessions of that group and posted them on YouTube. This in turn caused me to structure the meetings somewhat differently. The Classics group discussions are usually pretty freewheeling, and it doesn’t matter too much if we sometimes end up digressing. But the fact that hundreds and perhaps eventually thousands of people will be viewing the recordings of the Situationist sessions in years to come made it more important to keep the discussion focused. So I organized that series more like a webinar, in which I made introductory remarks and comments on the texts, followed by Q&A. The group went through all of the Situationist International Anthology and all of my annotated translation of Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, and also viewed and discussed two of Debord’s films. You can see the video recordings of all 29 of the Zoom sessions of this group here.

I have concluded that Situationist series, at least for the time being. The Classics group continues, meeting every other Sunday, 5:00-7:00 p.m. Pacific Time. Participation is free and all are welcome. Let me know if you’d like to take part in it.

Below are the previous readings of the group and the tentative upcoming schedule (with the number of meetings in brackets).

EXPLORING THE CLASSICS

2016

Cervantes, Don Quixote [12]

Montaigne, Selected Essays [10]

2017

Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel [6]

Bunyan, Pilgrim’s Progress [4]

Swift, Gulliver’s Travels [4]

Madame de Lafayette, The Princesse de Clèves [4]

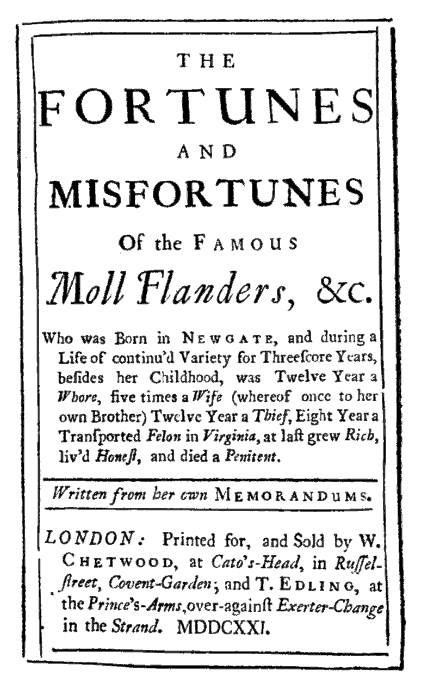

Defoe, Moll Flanders [4]

2018

Fielding, Tom Jones [7]

Sterne, Tristram Shandy [7]

Diderot, Jacques the Fatalist and His Master [4]

Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson (abridged) + Selected

Writings by Johnson [7]

2019

Stendhal, The Red and the Black [5]

Balzac, Lost Illusions [6]

Flaubert, Madame Bovary [5]

Marx, Writings on the French Revolution of 1848 [4]

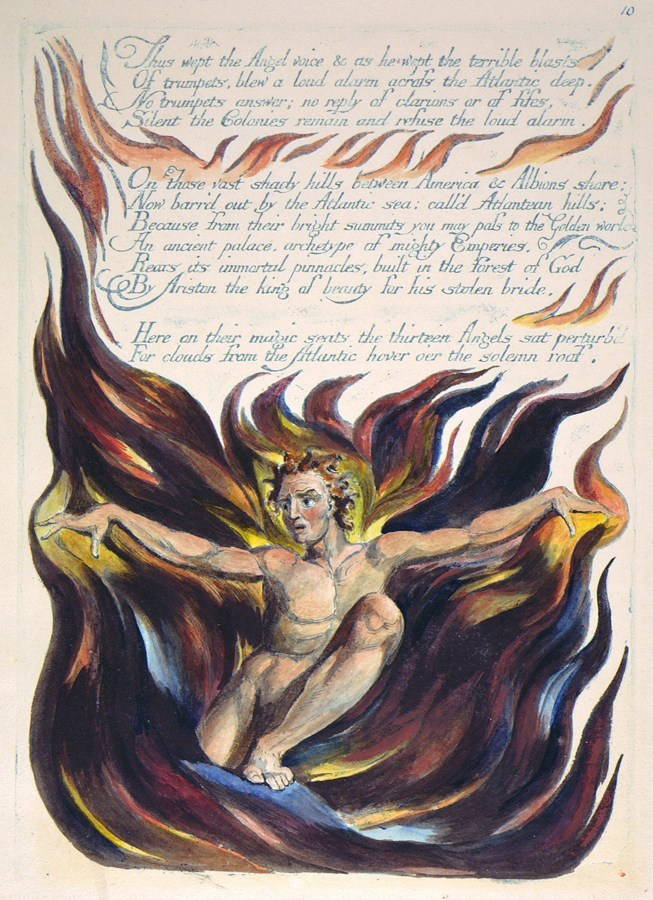

Blake, Selected Poems [4]

2020

Whitman, Selected Poems [4]

Baudelaire, Selected Poems [1]

[Meetings were suspended mid-March through June, then resumed via Zoom.]

Baudelaire, Selected Poems [4]

Rimbaud, Selected Poems + A Season in Hell [4]

French Poets 1850-1950 [5]

2021

French Songs 1800-2000 (“The Secret World of

French Songs”) [10] [These sessions were

recorded.]

Ford Madox Ford, Parade’s End [8]

Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook [5]

The Epic of Gilgamesh [2]

2022

Bhagavad Gita [2]

Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught [2]

Tao Te Ching [2]

Chuang Tzu [2]

Paul

Reps & Nyogen Senzaki, Zen Flesh, Zen Bones [2]

Shunryu Suzuki, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind [2}

Classic Chinese Poetry [4]

Basho, Selected Haikus + Narrow Road to the Interior [4]

Women Poets of Japan and China [2]

Tsao Hsueh-chin, The Dream of the Red Chamber (abridged) [3]

2023

Sappho, Poems [2]

Poems from The Greek Anthology [1]

Greek Drama [7]

Herodotus, The Persian Wars [6]

Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War (excerpts) [1]

Petronius, The Satyricon [2]

Apuleius, The Golden Ass [2]

Arabian Nights [3]

2024

The Kalevala [3]

Njal’s Saga [3]

Paul Radin, Primitive Man as Philosopher [2]

Paul Radin & James Johnson Sweeney (eds.), African Folktales and Sculpture [2]

Jaime de Angulo, Indian Tales [2]

Theodora Kroeber, Ishi in Two Worlds [1]

Kenneth Rexroth (ed.), The Poetry of Preliterate Peoples (unpublished

anthology) [3]

Shakespeare, Songs from the Plays [1]

Robert Burns, Selected Songs [2]

British Traditional Ballads [2]

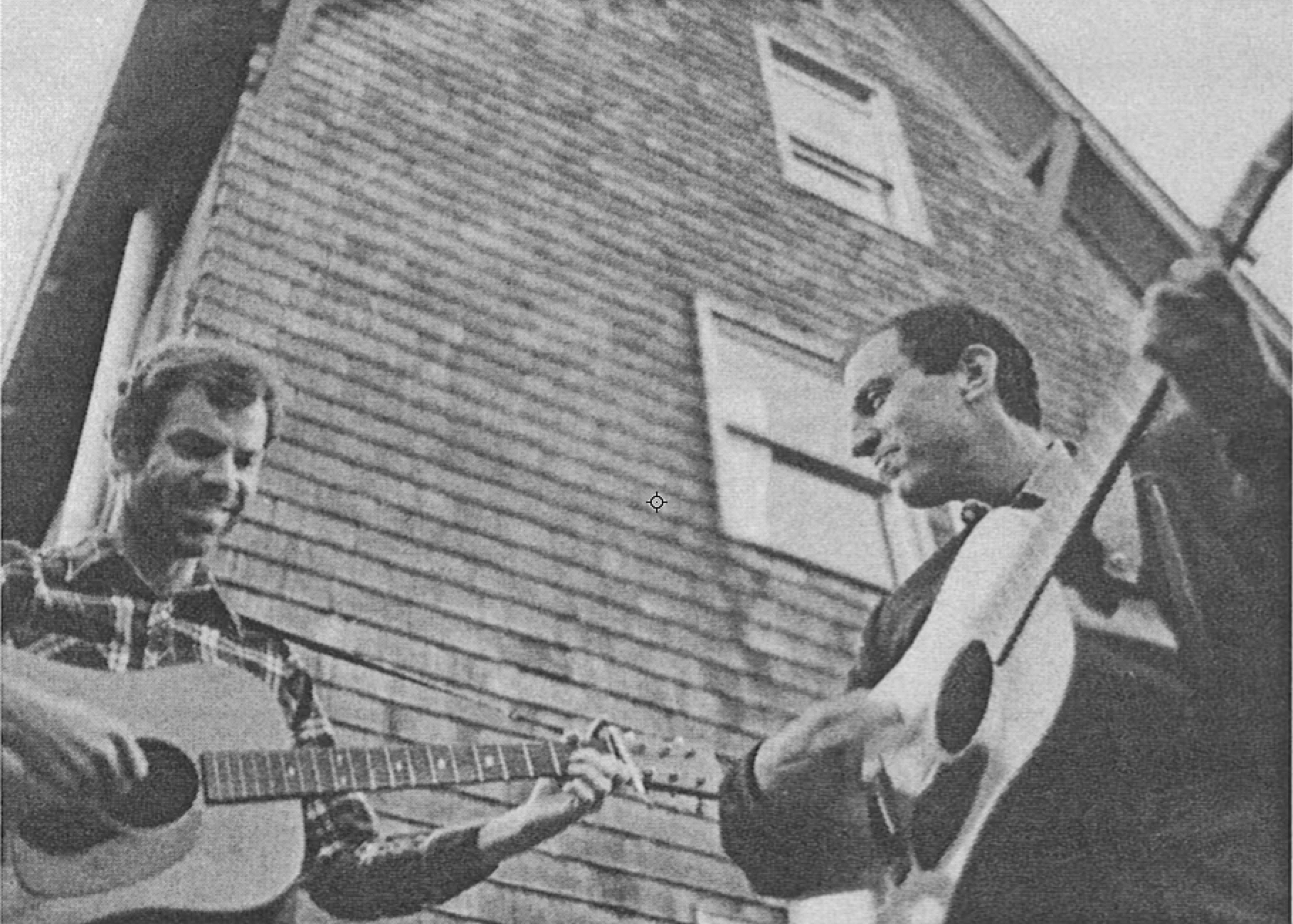

American Folksongs and Blues (“The Old

Weird America”) [6] [These

sessions were recorded.]

___________________________________________________

Meanwhile, during 2023 and 2024 I also led a parallel Zoom group

called

“Exploring the Situationists” (alternating Sundays with the “Classics”

group):

Situationist International Anthology [10]

Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle [15]

Guy Debord, Two Films [4]

These 29 meetings were recorded (see

www.bopsecrets.org/videos.htm).

___________________________________________________

2025

Emma Goldman, Living My Life (abridged) [4]

Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary [3]

Victor Serge, A Blaze in the Desert: Selected Poems [1]

George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia [2]

Mary Low & Juan Breá, Red Spanish Notebook [1]

Noam Chomsky, Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship [1]

Ngo Van, In the Crossfire: Adventures of a Vietnamese Revolutionary

[2]

Kenneth Rexroth, An Autobiographical Novel [5]

André Breton, Nadja [1]

George Orwell, Down and Out in Paris and London [1]

Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer [2]

Anaïs Nin, Henry and June [2]

2026

Martin Buber, I and Thou [3]

Martin Buber, The Way of Man According to the Teachings of Hasidism

[1]

Bertolt Brecht, Stories of Mr. Keuner [1]

Guy Debord, Complete Cinematic Works [4]

Ken Knabb, The Joy of Revolution and Related Texts [4]

Albert Cossery, The Jokers [2]

H.L. Mencken, The Vintage Mencken [3]

Kenneth Rexroth, Selected Essays [3]

2027

Paul & Percival Goodman, Communitas: Ways of Livelihood and Means of

Life [3]

William Morris, News from Nowhere and other writings [2]

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia [2}

Herbert Read, The Green Child [2]

B. Traven, General from the Jungle [2]

Kenneth Rexroth, Communalism: From Its Origins to the Twentieth

Century [3]

Marie Louise Berneri, Journey Through Utopia [3]

Friedrich Engels, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific [1]

Lewis Mumford, The City in History [6]

2028

Kenneth Rexroth, The Dragon and the Unicorn

[3]

Poetry Aloud (sometimes with jazz) (Rexroth, Patchen, Ferlinghetti,

Kerouac, etc.) [3]

Kenneth Rexroth, Selected Poems [2]

Allen Ginsberg, Howl and Other Poems [1]

Jack Kerouac, The Dharma Bums [2]

Gary Snyder, Earth House Hold [2]

Gary Snyder, Mountains and Rivers Without End [2]

. . . .

With the exception of the French Songs series in 2021 and the American

Folksongs series in 2024, I haven’t recorded any

of the above sessions, though it would have been easy enough to do this once we were on Zoom.

I felt that if the participants knew their remarks were being recorded

for posterity it would inhibit the discussion. And in any case,

interesting as the discussions often were for the participants, I

doubted if many other people would be all that interested in listening

to them.

Nevertheless, from time to time people have said they wished the meetings had been recorded, so they could check out meetings they’d missed, or refer friends to them. It eventually occurred to me that it might be worthwhile to post excerpts from some of the introductory remarks and follow-ups I sent out to the group, so that anyone who was interested could at least get some idea of the works we discussed and perhaps check out some of the other readings or links I recommended. This webpage is what I have come up with.

First, a little background:

My classes at Shimer College (1961-1965) had familiarized me with group discussions of classic works. But although I of course engaged in countless informal discussions of books with friends over the following decades, it was not until the new millennium that I once again took part in any ongoing groups. In 2003 Steve Zolno and I started a Shimer alum group in the Bay Area. We met every three or four months at one or another of our homes, spending the first hour chatting and sharing alum gossip and enjoying a potluck lunch, then two hours discussing some short text. We discontinued the group in 2024. You can see a list of the texts we discussed here.

In 2001, during one of my sojourns in Paris, I sat in on a discussion of Debord’s La Société du Spectacle. Soon after I returned to Berkeley a few friends said they wanted to start a group discussion of my translation of that same book. For the next year or two we met every other week in a Berkeley café, following the same close-reading procedure as the Paris group; and over the next few years I ended up facilitating several similar groups in the Bay Area, reading or rereading Debord’s book or articles from the SI Anthology or a few other related texts (Karl Korsch, Georg Lukács, etc.).

Overlapping with those discussions, I also took part in a “Dharma Literary Salon” with eight or ten Berkeley Zen Center friends. Although we were all Zen practitioners, we focused on Western literary works rather than Zen texts. From 2008-2011 we met once a month for potluck dinner and discussions. Eventually the group phased out and branched into two new groups:

One was led by the noted classical scholar Albert Dragstedt (husband of Naome Dragstedt, one of the Dharma Salon participants). This small private group met every other week at the Dragstedts’ home in Oakland, reading Greek classics (in translation) until Albert’s death in 2016. A few months later we resumed the group under the leadership of two of Albert’s classical-scholar colleagues, Theo Carlile and Jim Smith, and it has continued to meet at Naome’s home up to the present. Over the years we’ve gone through Homer, Herodotus, Thucydides, all the Greek tragedies, quite a bit of Plato, some Aristotle, Aristophanes, Euclid, and Sappho, and a few Roman works.

The other group was led by another Dharma Salon participant, Patrick McMahon. Patrick had talked with Bill McClung, cofounder of University Press Bookstore in Berkeley, and arranged for us to meet every other week in the back room of the bookstore to explore Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (a.k.a. Remembrance of Things Past). Going through that immense work at an appropriately leisurely pace took us four years (2011-2015). It was a very enjoyable experience, including not only the interesting discussions in the pleasant ambience around the big table in the back of the bookstore (see the above photo) but also other gatherings among the participants (parties, concerts, films, etc.). Around twenty-five people took part at one time or another, but a core group of nine of us were there pretty much from start to finish.

As we approached the end of the Proust project, we started to think

about where we wanted to go next. Patrick was in favor of

spending another two or three years on some similarly lengthy project, such

as Dante’s Divine Comedy or Joyce’s Ulysses. I was

in favor of exploring a greater variety of works. This debate

continued over several months, with other group participants

suggesting many different possibilities. Seeking to bring a little

order into the discussion (more than thirty books had been suggested), I proposed that

the core group vote on their

top favorites. We did this and it did indeed narrow the field

somewhat, as several of the books (or themes or genres)

nominated didn’t get many votes. We then had the meeting

described in the following email by one of the core participants, Rob Lyons.

[November 24, 2015]

Recap of Sunday conversation

Hey all,

Six of our “little band” were able to meet this morning at UPB, beginning at 11 am: Bill M., Bill G., Patrick, Ken, Richard, and myself.

Patrick began began by reminding us all of the group’s history and making a valuable distinction between a “book group” that jumps from one book to another, and a “study group” that allows for deeper readings, supplementary material, and more probing examination of the text. We went around the table, and each of us in turn spoke about what we hoped for with regard to our next reading project. There was general agreement with Patrick’s “study group” principle; and also that a two-year project seemed about right (not too long, not too short).

Ken was appreciated by all for the work he did over the past week conducting the “straw poll” of individual preferences — which required extensive email and phone communication with our far-flung group.

Ken passed out a sheet that summarized the seven “clusters” that had been identified in recent weeks:

1. Ulysses + Odyssey + Hamlet

2. Divine Comedy

3. Spanish/Latin American

4. Japanese

5. Russian

6. Humanist Classics

7. Modern Fiction Classics

Richard reviewed for our benefit the vote tally from the “straw poll.” Although there was a short discussion about the possibility of selecting the top vote-getters, which would have resulted in a potpourri of works from different periods and/or genres, there was broad acceptance of the “cluster” concept as a guiding principle. Several approaches to clustering were discussed, for example picking works of a common nationality and/or language, and picking works that were of the same era, or philosophical outlook or genre (picaresque novels, for example).

The rest of the discussion focussed on the seven clusters that Ken had listed. We began by setting aside those clusters that seemed to have the least appeal or that would present particular problems: the Japanese cluster because the Tale of Genji would require perhaps too much depth and specialization in its study; the first two (Ulysses et al, and the Divine Comedy) because there might be one or more group members who would pass on reading them (and would for that reason leave the group). Also the Modern Fiction Classics cluster was thought to be a cluster in name only, with limited connections among the various works.

Which narrowed the choices to three: Spanish, Russian, and Humanist. Rob gave a quick spiel on the Spanish and Russian clusters, and Ken gave an impassioned argument for the Humanists, which among other things included a definition of the term “humanist” (his explanation made sense to us at the time, but we may ask him to reiterate it in a follow-up email). Although the works listed were from three nations (Spain, England, and France), they were nevertheless linked by a common sensibility and outlook; they were for the most part comedic (as well as bawdy, absurd, joyous, sly); and all descended from or related in some fashion to Don Quixote:

Cervantes, Don Quixote

Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel

Montaigne, Essays

Sterne, Tristram Shandy

Fielding, Tom Jones

Boswell, Life of Samuel Johnson

Patrick noted that the leading advocate for the chosen cluster might reasonably be expected to act as the group leader and organizer, which Ken offered to do if the Humanist cluster were chosen. Rob threw his support behind Ken as group leader. Bill M. proposed that Ken be appointed Master of the Universe. Ken vowed to include others in supporting roles along the way, in a manner similar to that employed by Patrick in the later stages of the Proust project.

And so it came to pass that the Humanist Cluster was chosen, and Ken named as our leader.

All present were pleased and satisfied with the outcome. We agreed to share the results of our discussion with the three group members who were unable to participate — Maureen, Sandy, and Al — and ask if they had concerns or misgivings about the process we followed or its outcome. Please let us know by follow-up email how you feel about the plan, and if you object or concur.

It was agreed (pending confirmation by the three absent members) that we would begin with Don Quixote. The first group meeting will take place in January. The exact contents and sequence of readings after Don Quixote will be discussed at a future date: some suggested additions included Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist, Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and The Manuscript Found at Saragossa.

Sunday December 13 was selected as the date for the Proust Group Holiday Party; Rob volunteered his house as the venue. Party details will be discussed in subsequent emails.

All in all, a very fruitful discussion. Thanks to all for your participation and contributions!

Rob

NOTE: From here on I will be reproducing excerpts from some of the email

announcements I sent out relating to this new book group. Some

were general announcements of upcoming readings sent to several hundred local

friends; others were sent only to those who had signed up to take part in

particular readings. I have left out most of the routine logistical details and focused on

links and other information that I think might be of interest to

people who were not at the

discussions (or even to those who were there but who might like to have

them conveniently available for future reference). I have not indicated

the omissions, and I have also silently made a few minor

corrections and revisions (e.g. adding some links and references that I’d forgot to

include in the original emailing or that I later discovered) — all with the aim of making this chronicle more

useful and more readable.

I at first referred to the series as “Quixote & Friends,” but

eventually decided to call it “Exploring the Classics.” As will become

evident, my main inspiration throughout this whole venture has been Kenneth Rexroth’s

Classics Revisited.

Don Quixote reading group

Dear Bay Area Friends,

Beginning January 17, I will be facilitating a reading and discussion of Cervantes’s Don Quixote. The group will meet every other Sunday at 4:30-7:00 p.m. in the University Press Bookstore (2430 Bancroft, Berkeley). Proceeding at a steady but leisurely pace appropriate for following the unhurried wanderings of the starry-eyed knight and his down-to-earth squire, we should arrive at the end of our journey in around five or six months. At which point we will embark on another one.*

Participation is free, but donations of $10 or so are suggested to help support the bookstore, which will be providing us with a pleasant meeting space and complimentary tea, wine, sandwiches, and cookies.

It should be fun! Please let me know if you’d like to join us.

Ken Knabb

___________

*Don Quixote is the first in a series of classic works that we will be exploring over the next two or three years, which will include Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel, Montaigne’s Essays, Fielding’s Tom Jones, Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist, and Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson.

[December 15, 2015]

Don Quixote translations

Dear Quixotistas (fervent or potential),

There has been a gratifyingly enthusiastic response to the news of our Don Quixote reading group, and I have already received a number of queries about which translation we will be using.

The short answer is: We will be using multiple translations. I recommend John Rutherford’s and Samuel Putnam’s, but you are welcome to use any other version you may prefer.

The longer answer is: Twenty different translations of Don Quixote have been made into English. None is entirely satisfactory. The older ones are in dated language and many of them are also rather free. The newer ones are more accurate, but none has the vigor of the original (as far as I can tell, knowing very little Spanish). So we’re going to make a virtue of necessity and use a variety of translations. We will still all be reading the same book, but when we read passages aloud in the group we can examine any notable differences among the different versions, thereby also getting a keener sense of the issues involved in literary translation.

For comparison, I have posted thirteen versions of the famous Windmill episode — all eight modern ones plus five of the most significant earlier ones — along with the original Spanish: www.bopsecrets.org/gateway/passages/don-quixote.htm

Samuel Putnam’s translation, the first of the modern ones (1949), has been reprinted in numerous editions and has been the closest thing to an acknowledged standard version during the last 65 years. It is still probably the best written, but it is now challenged by some of the more recent versions. John Rutherford’s translation (Penguin, 2000; not to be confused with the earlier Penguin edition translated by J.M. Cohen) is the most idiomatic, which is particularly important in rendering Sancho’s folksy sayings and opinions. Burton Raffel’s is among the most rigorous in tracking the original Spanish, and his edition also contains the most extensive supplementary materials (Don Quijote: A Norton Critical Edition, 1999). But the other modern translations also have their merits and their fans, and the differences between them are mostly rather subtle.

I recommend that you get the Rutherford or the Putnam translation, in addition perhaps to Raffel’s edition for purposes of comparison and for the supplementary texts. But if you prefer one of the other modern versions — Cohen, Starkie, Grossman, Lathrop, or Montgomery — that will be fine, too. (For historical contrast we will occasionally look back at two or three of the earlier translations, but I don’t think anyone will want to use any of those versions for their main reading.)

University Press Bookstore (where we will be meeting) has ordered a bunch of the Rutherford translation; they should be in the store sometime next week. The Putnam version is widely available — online, at most libraries, and in many bookstores (there were several copies at Moe’s the last time I looked).

Also, if you know any Spanish, what better way to brush up on it than to get a Spanish edition to dip into from time to time? If you are a native Spanish speaker, all the better! We hope you will join us to help elucidate the finer points of the book.

Our first meeting is still over a month away (January 17), but you may want to take advantage of the holidays to get your copy and start reading ahead. We will be reading 80-100 pages every two weeks for the next five or six months.

We’ll be meeting in the back room of University Press Bookstore (2430 Bancroft in Berkeley). Meetings will begin with an informal period of tea, wine, sandwiches, cookies, and socializing from 4:30 to 5:00. The book discussions will start at 5:00 sharp and go till 7:00.

Cheers,

Ken

2016

Montaigne Reading Group

Dear Bay Area Friends,

Beginning July 17, I will be facilitating discussions of selections from Montaigne’s Essays. The group will meet for ten sessions, every other Sunday at 4:30-7:00 p.m. in the University Press Bookstore (2430 Bancroft, Berkeley), ending November 20. At that point we will take a holiday break, then resume our series in January.* Please let me know if you’d like to join us.

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) virtually invented the essay. The French word essai originally had nothing to do with literature; it meant assay, assessment, attempt, test, trial, experiment. Montaigne applied the term to his writings because he intended them as exploratory ventures — attempts to find out about himself by examining his reactions to various subjects (and vice versa), keeping an open, almost childlike mind and seeing where things would lead. Taken as a whole, his leisurely and seemingly rambling observations form a candid self-portrait of a kind that had never been seen before. You get to know a real person rather intimately, and he is a very pleasant person to know. “That such a man wrote has truly augmented the joy of living on this earth” (Nietzsche).

We will primarily be using the Penguin edition of the Complete Essays translated by M.A. Screech, but the Donald Frame translation is also excellent – you are welcome to use that or any other edition you may have (we will occasionally compare the two versions). The bookstore has several copies of the Penguin edition.

The readings for our first meeting are “On Presumption” (Book II, #17) and “On Repenting” (Book III, #2). In these two essays Montaigne tells us how and why he is undertaking these unprecedented self-explorations.

If you would like to do some background reading, I recommend Donald Frame’s Montaigne: A Biography and Sarah Bakewell’s How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer. The first is a straight bio, the second a more thematic study. Both can be ordered online, and the bookstore has a few copies of the Bakewell.

_____________________

*In our “Quixote & Friends” series

we are exploring these eleven classic

works: Cervantes’s Don Quixote

(which we just finished),

Montaigne’s Essays

(selections), Rabelais’s

Gargantua and Pantagruel, Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s

Progress, Swift’s

Gulliver’s Travels, Madame de Lafayette’s The Princesse de Clèves, Defoe’s

Moll Flanders, Fielding’s

Tom Jones, Sterne’s

Tristram Shandy, Diderot’s

Jacques the Fatalist, and

Boswell’s The Life of Samuel

Johnson.

[August 10, 2016]

A reminder that our next Montaigne discussion will be this Sunday, August 14. We will be discussing three essays: “On Friendship” (Book I, #28), “On Three Kinds of Social Intercourse” (Book III, #3), and “On the Art of Conversation” (Book III, #8).

For those of you who have the Bakewell book, Chapter 5 discusses Montaigne’s great friend Étienne de La Boétie, who is mentioned frequently in the “Friendship” essay. At the meeting C.S. will give a short report on La Boétie’s Discourse on Voluntary Servitude.

Also, Nannick will be bringing her sister Babelle (here on a visit from France) and another French friend, so we’ll have plenty of opportunity to hear how some of Montaigne’s passages sound in French!

[August 30, 2016]

I’ve just uploaded six different translations of a passage from Montaigne: www.bopsecrets.org/gateway/passages/montaigne.htm

You might also be interested in this article by Stephen Greenblatt about Montaigne’s influence on Shakespeare (via the 1603 translation by John Florio) — www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/10877821/Stephen-Greenblatt-on-Shakespeares-debt-to-Montaigne.html. Shakespeare almost certainly knew Florio personally, and his Montaigne translation is one of the few books we know for certain that Shakespeare owned.

See also Rexroth’s essays on

Montaigne, Don Quixote,

and Rabelais’s Gargantua

and Pantagruel —

www.bopsecrets.org/rexroth/cr/6.htm

[November 21, 2016]

Dear All,

Just a reminder that our next and final Montaigne

meeting will be this Sunday, November 20.

We will be discussing

Montaigne’s last essay, “On Experience”

(Book III, #13), which in many ways sums up

his entire venture. It will be a good way to wind up our

exploration of this wonderful man, who Orson

Welles called “the greatest writer of any time, anywhere.”

We will be having a joint year-end party

with participants from several other reading

groups on Sunday, December 11 (details to

come), then take a holiday break, then

resume on January 15 with Rabelais’s

Gargantua and Pantagruel.

I hope you all are recovering from the

election shock. I think there are two

interconnected ways to deal with this

bizarre new situation: (1) Fight back, and (2) Continue to pursue lives as full of humanity

as possible. For me, these discussions of

some of the great expressions of what it

means to be human are a big part of the

second aspect.

Cheers,

Ken

Rabelais Reading Group

Dear Bay Area Friends,

Beginning January 15, I will be facilitating

discussions of Rabelais’s Gargantua and

Pantagruel. The group will be meeting

every other Sunday at 4:30-7:00 p.m. in the

University Press Bookstore (2430 Bancroft,

Berkeley).

Rabelais’s work consists of five relatively

independent “Books.” We will be reading at

least the first two Books, which will take

four meetings (ending on February 26). If

participants remain enthusiastic, we will

continue with some or all of the later

Books. If participants feel like they’ve had

enough, we will instead move on to the next

works in our series.

François Rabelais (c. 1483-1552) created one of the most bawdy and exuberantly funny books ever written. Full of extravagant wordplay that would not be equaled until Joyce, this literally “larger than life” story of two giants satirizes law, education, politics, philosophy, religion, and just about everything else, and even sketches a quasi-anarchist utopia (the Abbey of Thélème, with its motto: “Do as you wish”).

“The Adventures of Gargantua and Pantagruel is a manifesto of sanity, health, and general moral salubriousness. Few books in history are more well, no characters in all literature less sick than those genial giants and their companions. This is the secret of the book. Rabelais used the broadest farce, the coarsest slapstick, to portray that primary ideal of the Renaissance, man at his optimum. . . . What does man do at his optimum? He creates. He uses his mind and body to their fullest capacities. His curiosity is always busy. He works with joy. Joy; one thing man certainly does when living at his fullest potential is laugh, and for very simple reasons.” (Kenneth Rexroth)

We will be using the Norton edition translated by Burton Raffel, and the Penguin

edition translated by M.A. Screech. The bookstore will soon have several copies

of both. I slightly prefer the Raffel translation, but the Screech version has

more useful notes, so look them over and take your pick. You are also welcome to

use any other edition you may have. You can sample eight different translations

of one of the chapters

here.

2017

[January 8, 2017]

Introductory remarks on Rabelais

Welcome to our Rabelais Reading Group. The first meeting will be January 15.

As we begin this unique and wonderful work, I’d like to make a few points.

Rabelais’s book is recognized as one of the major classics of world literature, and it has continued to be popular for centuries. But there’s no denying that some parts of it are now pretty obscure for modern readers, especially in translation.

In our first reading assignment (Gargantua, chapters 1-24), for example, Chapter 2 is so obscure that even scholars are not sure what it’s all about. Feel free to skim it, or even to skip it. Most of the other chapters are generally comprehensible, but you should be aware that we’ll inevitably be missing a lot of the nuances. It’s clear enough, for example, that Chapters 14 and 15 are satirizing an old-fashioned type of education, which is contrasted with the more modern, Renaissance/Humanist style described in later chapters; but the details depend on some knowledge of Latin and of medieval philosophy and educational practices. The same goes for Chapters 18-20, which satirize the academic jargon of the dogmatic professors of the Sorbonne, as exemplified in the speech by Master Twosides (a.k.a. Janotus de Bragmardo). You can imagine how difficult it is to translate such passages so they’re as funny as they are (or were), in the original. In other cases, the problem may be the topic. Chapters 9 and 10, which deal with color symbolism, which was apparently a popular and much-debated topic in Rabelais’s time, will probably seem less interesting to you, as they do to me. (But maybe that’s just my blind spot: perhaps more visually oriented readers will find these chapter more interesting than some of the others.)

I think you will find that the long lists, which may look rather tedious on the page, will come alive when you read them out loud. Rabelais is one of the world’s most sprawling and exuberant writers, and a large part of his “message” is communicated in this manner. In this way he’s kind of like Whitman, whose long lists of things are also a lot more vivid and exciting when read aloud.

There is also the obvious fact that Rabelais is far from politically correct. This should not be shocking news for any historically literate person. We may note some of these flaws in passing, but if such things really bother you, you will be better advised to go elsewhere. We’ll be taking a wild, rambunctious ride through a world that is larger and more all-inclusive than any quibbles we may have.

This is all to say: Don’t worry too much! When you come across something you don’t understand, or something that seems uninteresting or dubious, move on to the next paragraph or the next chapter. Most of the book is about qualities that are pretty much universal, human foibles and social absurdities that aren’t much different now than they were in Rabelais’s time. Imagine if he were to return to life and we were to point out some of the shortcomings of his writings or his era. I can see him replying: “Worthy ladies and gentlemen, you may be right! I’m willing to learn! For purposes of comparison, could you tell me how your country is currently governed?”

At the meeting we will be reading aloud the Author’s Prologue and Chapters 6, 11, and 23, but we’ll also be briefly discussing some of other themes mentioned above, as well as the original contexts of Rabelais’s work.

I am aware that some of you only recently found out about the group and have not yet had time to do the reading. Don’t worry! This first meeting will be mainly introductory, and we will mainly be discussing the passages that we have just read aloud. So please come regardless. If you haven’t already got a copy of the book, you can buy one right there at the bookstore (which has both the Raffel and Screech versions).

Till then, as Rabelais himself urged us: Be Happy!

Ken

[February 13, 2017]

Some good books on Rabelais and his time:

Donald Frame, Francois Rabelais (good basic presention)

M.A. Screech, Rabelais (the most detailed analysis)

Wyndham Lewis, Doctor Rabelais (insightful but idiosyncratic — Lewis is kind of like Ezra Pound)

Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World (focuses on the carnivalesque/folk-culture aspects; that theme is important but the author is rather repetitious)

Also: Chapter 32 is discussed in detail in Erich

Auerbach’s Mimesis: The Representation of Reality

in Western Literature. I highly recommend

Auerbach’s book, which also contains really

interesting essays on Homer, Montaigne, Don

Quixote, Virginia Woolf, and many other classic works. At our next

meeting I’ll be reading aloud several

passages from Auerbach’s chapter on Rabelais.

NOTE: Meanwhile, there were other book groups going on at

the same bookstore. Bob Meyer led a two-year reading of Joyce’s

Ulysses; Patrick McMahon led a series on shorter works by Joyce and

Virginia Woolf;

Richard Zuckerman led a small group rereading portions

of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time; Brenda Hillman led

discussions of Emily Dickinson; Lois Potter and Joel Altman led

discussions of Shakespeare’s sonnets. There was quite a bit of overlapping among

participants of all these groups and the “Exploring the Classics” one.

(I took part in the Ulysses, Dickinson, and Shakespeare groups —

a pleasant change to simply reading and discussing while someone else

took care of all the preparation and facilitating!)

Better than Shakespeare?

Dear Bay Area Friends,

Beginning April 9, I will be facilitating discussions of John Bunyan’s book The Pilgrim’s Progress. The group will be meeting every other Sunday at 4:30-7:00 p.m. in the University Press Bookstore (2430 Bancroft, Berkeley) for four meetings (April 9 and 23, May 7 and 21), then in June we’ll move on to the next work in our series.* Participation is free, but donations of $10 or so per meeting are suggested to help support the bookstore, which will be providing us with a pleasant meeting space and complimentary tea, wine, sandwiches, and cookies. Please let me know if you would like to join us.

George Bernard Shaw said that Bunyan was “England’s

greatest prose writer” and that The Pilgrim’s

Progress was “better than Shakespeare.” A bit of

an exaggeration, perhaps, but not by much. Although

it is marred for modern readers by its harsh

Biblical worldview, The Pilgrim’s Progress is

nevertheless a truly marvelous book. The characters,

despite their allegorical names, are more vivid than

in almost any novel. If you make a little mental

adjustment, the book does not seem all that dated.

We are still living in a world full of Cities of

Destruction and Vanity Fairs, struggling over the

Hill Difficulty and through the Valley of the Shadow

of Death, hoping to eventually find our way to the

Delectable Mountains, but meanwhile coming upon

characters like Mr. Talkative, Madam Bubble, Mr.

Hypocrite, Mr. Pliable, Mr. Legality, Mr. Malice,

Mr. Money-Love, Mr. Worldly-Wiseman, Parson

Two-Tongues, Lord Fair-Speech, and Lady Feigning, but

occasionally also a Miss Mercy or a Mr. Great-Heart.

In our discussions we will also be noting the

elements of social critique in Bunyan’s book.

Such elements were perforce carefully disguised

or played down — the book was written while

Bunyan was in prison, and even when he got out

there was widespread censorship — but the book

definitely reflects the tumultuous experiences

of the English Revolution (1640-1660).

_______________

*Exploring the Classics is an ongoing series, led by Ken Knabb and hosted by University Press Bookstore, in which we are exploring these classic works: Cervantes’s Don Quixote, Montaigne’s Essays, Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel, Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Madame de Lafayette’s The Princesse de Clèves, Defoe’s Moll Flanders, Fielding’s Tom Jones, Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist, and Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson.

_______________

* * *

I have been asked to explain how this

particular list was chosen. A year and a half ago,

as we neared the end of our four-year Proust

exploration at University Press Bookstore, we

debated where to go from there. There was a general

desire to continue with another multiyear project,

either an intensive study of one very long work or a

slightly more rapid exploration of a series of

related works. I was in favor of the latter idea.

When our group did a preliminary vote for favorites

among some thirty works that had been nominated, I

pointed out that six of the top vote-getters were in

the same general period (16th-18th centuries) and

were akin in many ways — Gargantua and Pantagruel, Montaigne’s

Essays, Don Quixote, Tom Jones,

Tristram

Shandy, and Boswell’s Life of Johnson —

and would thus make a very nice series. After some

discussion, my proposal was unanimously agreed to,

on the condition that I would take the

responsibility of leading it. I happily agreed to do

this since I was enthusiastic about all of these

works. (Organizing these discussions is a labor of

love for me. I don’t receive any remuneration; the

donations all go toward helping the bookstore stay

in business.)

In addition to the six above-mentioned works (all

rather lengthy), I’ve added a few shorter works that

fill in and illuminate the interconnections: Pilgrim’s Progress and

Gulliver’s Travels,

two satirical journeys through human society in the

tradition of Rabelais and Don Quixote; and

two other works that mark important stages in the

early development of the novel: The Princesse de

Clèves and Moll Flanders. The

Princesse de Clèves is the first

subtle psychological novel (apart from The Tale

of Genji, also written by a woman) and thus the

ancestor of Stendhal, Flaubert, Proust, Henry James,

etc., while Defoe, whose vivid colloquial style was

influenced by Bunyan, is the ancestor of all

subsequent “realist” fiction. The realism of Tom

Jones (yet another “journey” story) is

continually disrupted by the author’s amusing

comments. Just as amusing but much more mentally

disruptive, Tristram Shandy draws on all the

earlier works mentioned and its narrative techniques

foreshadow Joyce and Virginia Woolf. I’ve also added

Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist since it was

directly inspired by Sterne’s book. Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, often considered the

greatest biography ever written, provides a

magnificent nonfictional perspective on the

18th-century British world portrayed by Defoe,

Fielding, and Sterne.

Our group has already had a lot of fun exploring

Don Quixote and Montaigne’s Essays, and

we’re just about to finish Rabelais. Pilgrim’s

Progress, Gulliver’s Travels, The Princesse de Clèves,

and Moll Flanders will take about two months

each, bringing us to the end of this year. Tom

Jones, Tristram Shandy, and Jacques the

Fatalist will take us through most of 2018.

Boswell’s Life of Johnson will extend into

the beginning of 2019.

I encourage you to participate in any or all of

these explorations.

Ken

[April 10, 2017]

I’m gratified that our first Pilgrim’s

Progress meeting went so well. I had been

worried that people might be put off by the book’s

religious worldview, but my sense is that just about

everybody left the meeting enthused about the

vividness of the book’s characters, the liveliness

of the narration, and the intensity of the vision.

Some relevant texts and links

I mentioned at that

meeting (these readings are all optional, I mention

them simply in case you wish to pursue any of these

topics):

Dorothy Van Ghent’s The English Novel includes essays on Don Quixote, Pilgrim’s Progress, Moll Flanders, Tom Jones, Tristram Shandy, and a dozen others (Austen, Dickens, Hardy, Conrad, Lawrence, Joyce, etc.).

Christopher Hill’s The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution. My brief review of Hill’s book is at www.bopsecrets.org/recent/reviews.htm

For more on the radical elements of the English Revolution (1640-1660), see the chapter on the Diggers in Rexroth’s Communalism: From Its Origins to the Twentieth Century — www.bopsecrets.org/rexroth/communalism4.htm. Bunyan was not exactly a proponent of these extremist radical currents, but he lived among them and they certainly influenced his social views.

Rexroth’s essay on Pilgrim’s Progress — www.bopsecrets.org/rexroth/cr/6A.htm#Pilgrims-Progress

For comic relief, see also Hawthorne’s story “The Celestial Railroad” — https://pinkmonkey.com/dl/library1/haw15.pdf

[May 12, 2017]

Exploring the Classics

Dear Bay Area Friends,

During the last several years I’ve taken part in a number of book discussion groups. Some have dealt with radical works such as Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle or selected articles from the Situationist International Anthology. Others have examined various literary classics, from Homer and Shakespeare to Proust and Joyce. These two types of groups involve rather different aims and attitudes, but I like to think of them as complementary. The first type focuses on radical tactics and strategy — how we might better understand and transform the absurd social system in which we find ourselves. The second is more leisurely and open-ended — exploring and enjoying imaginative works that enliven and potentially illuminate our lives in general.

Recently I’ve been leading one such group at the University Press Bookstore in Berkeley. During the last year and a half we’ve gone through Cervantes’s Don Quixote, Montaigne’s Essays, Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel, and Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and are about to continue with Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Madame de Lafayette’s The Princesse de Clèves, Defoe’s Moll Flanders, Fielding’s Tom Jones, Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist, and Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson.

To my taste, few things in life are more consistently enjoyable than discussing these kinds of works with congenial companions, preferably accompanied by good food and drinks. That’s the original sense of the word symposium (“banquet”), as in Plato’s dialogue of that name, where Socrates drinks all his companions under the table as they debate the nature of love far into the night.

Our gatherings don’t last quite that long and we don’t drink quite that much, but the discussions are just as lively. We are exploring these books because they continue to be relevant. They continue to engage us because they address the perennial life issues that we all face in one way or another. They raise difficult questions rather than offering easy answers. They may not tell us what to do about our specific situations, personal or political, but they help provide a broader context for whatever decisions we do make, giving us a better sense of the varieties and potentialities of human experience, from the sublime to the ridiculous.

And contrary to popular misconception, they are also among the most entertaining books ever written. If they weren’t, they wouldn’t have continued to be eagerly read and reread by countless people over the centuries.

Our discussions take place every other Sunday, 4:30-7:00 p.m., at the University Press Bookstore (2430 Bancroft in Berkeley). Participation is free, but donations of $10 or so per meeting are suggested to help support the bookstore, which provides us with a pleasant meeting space and complimentary tea, wine, sandwiches, and cookies.

Let me know if you’d like to join us.

Ken

Gulliver’s Travels

“If I had to make a list of six books which were to be preserved when all others were destroyed, I would certainly put Gulliver’s Travels among them.” (George Orwell)

This Sunday (June 4) we will begin our exploration of Jonathan Swift’s satirical masterpiece, Gulliver’s Travels. Its portrayal of humanity is so scathing that it might be considered the ancestor of black comedy, but most of the things Swift attacks are in fact pretty universal and undeniable — human foibles and social absurdities that aren’t much different now than they were in his time.

Imagine if Swift were to return to life in 2017 America and we were to tell him that he exaggerated the failings of humanity. I can see him replying: “Ladies and gentlemen of this strange future land, you may be right! I thought there were a lot of absurdities in my time and I attacked them accordingly. But perhaps things have improved since then. For purposes of comparison, could you tell me how your country is currently governed?”

Three very interesting essays on

the book:

A short one by Rexroth:

www.bopsecrets.org/rexroth/cr/6A.htm

A long one by Orwell: http://orwell.ru/library/reviews/swift/english/e_swift

A

review by Fintan O’Toole: “Swift: The Genius of Creative

Destruction”:

www.nybooks.com/articles/2013/12/19/jonathan-swift-genius-creative-destruction/ This latter is a good refutation of

the traditional portrayals of Swift

as insane, sexist, perverse,

misanthropist, etc., and at the same

time a favorable review of Leo

Damrosch’s recent biography of

Swift, which I also recommend.

Princesse de Clèves reading group

Dear Bay Area Friends,

Beginning July 30 I will be facilitating discussions of Madame de Lafayette’s short novel, The Princesse de Clèves.

First published anonymously in 1678, Madame de Lafayette’s The Princesse de Clèves marked a turning point in the history of literary fiction. In retrospect, it can be seen as the first subtle psychological novel (with the one notable exception of The Tale of Genji, also written by a woman) and thus as the ancestor of Stendhal, Flaubert, Proust, Henry James, and Virginia Woolf. But it’s more than a mere ancestor. Page for page, it’s as pithy as any of those later authors and far more concise (a mere 150 pages). We will thus be doing a particularly close examination, reading numerous passages aloud, consulting the original French version, clarifying the historical contexts, analyzing the moral dilemmas, and savoring the complex psychological nuances of this remarkable little book.

Please let me know if you’re interested in joining us.

Moll Flanders reading group

Dear Bay Area Friends,

Beginning September 24, I will be facilitating discussions of Daniel Defoe’s novel Moll Flanders. We’ll be using the Penguin Classics edition, edited by David Blewett (copies are available in the bookstore). Please let me know if you’d like to join us.

Soldier, speculator, and secret agent, Daniel Defoe (1660-1731) was also one of the most prolific authors of all time. In addition to editing more than a dozen newspapers, composing answers for some of the first advice columns, and writing hundreds of articles, pamphlets, and books on politics, economics, geography, religion, marriage, manners, morals, crime, psychology, superstition, and many other topics, he also authored a number of fictional works that are at the origin of the English novel, two of which have remained deservedly popular for nearly 300 years: Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Moll Flanders (1722).

“In Defoe’s novels everything is stripped to the bare, narrative substance, and it is this that reveals the psychology or morality of the individual. The most significant details are purely objective, exterior. The interiority of the characters is revealed by their elaborately presented outside. When they talk about their own motives, their psychology, their morals, their self-analyses and self-justifications are to be read backwards, as of course is true of most people. . . . Defoe was perfectly conscious of the parallel he was drawing between the morality of the complete whore and that of the new middle class which was rising around him, yet he remains aware of Moll Flanders as a woman of flesh and blood, and we in turn are aware of her. She comes to life in our minds as clearly as Chaucer’s wife of Bath. . . . When we come to the end with Moll, old, comfortable, and probably fat, and look back over a long life that came so often so near to total disaster, we think, ‘Well, old girl, you sure pulled a fast one.’ ” (Kenneth Rexroth)

Tom Jones reading group

Dear Bay Area Friends,

Beginning November 19, I will be facilitating discussions of Henry Fielding’s novel Tom Jones. The group will be meeting every other Sunday at 4:30-7:00 p.m. in the University Press Bookstore (2430 Bancroft in Berkeley) for seven meetings (November 19, December 3 and 17, January 14 and 28, February 11 and 25), followed by an eighth meeting (March 11) when we’ll watch Tony Richardson’s delightful film of the book. Then we’ll move on to the next work in our series. We’ll be using the Penguin Classics edition, edited by Keymer and Wakely (copies are available in the bookstore). Please let me know if you’d like to join us.

Henry Fielding’s lusty “comic-epic in prose” is one of the most entertaining books ever written. He declared that his subject was nothing less than “HUMAN NATURE” in all its variety, and few other writers besides Chaucer or Dickens could justify such a claim so well. Adding to the fun is the author’s periodically stepping back from the narration to give his own ironic comments on the characters and their adventures.

“Tom Jones has been compared to Odysseus and Huck Finn. Huck he somewhat resembles; Odysseus not at all. He is more like a compound of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza — not a mixture, but a chemical compound of antagonistic qualities and virtues which has produced a new being. The book is an immense panorama of mid-eighteenth-century England, as populous as any novel of Tolstoy’s or Dostoievsky’s. Comparison, however, with a work like War and Peace immediately reveals a profound difference. The plot of Tom Jones is not a ‘real life’ story but a fairy tale, disguised with realism. But it is not naturalism, and it is realism only in the broadest sense. It is an immensely complicated farce. This all gives the book an air of quiet madness.” (Kenneth Rexroth)

[December 17, 2017]

Dear Jonesians,

Following a holiday break, our next Tom Jones

meeting will be Sunday, January 14.

For those of you who have the time and interest, here are some recommended secondary readings:

Martin Battestin, Henry Fielding: A Life (the definitive biography, superseding several earlier ones)

Martin Battestin (ed.), Twentieth Century Interpretations of Tom Jones: A Collection of Critical Essays

Robert Alter, Fielding and the Nature of the Novel (good general analysis, including refutations of some critics’ disparagement of Fielding)

Henry Fielding, Joseph Andrews (Fielding’s other great novel, shorter but similar in many ways to Tom Jones; some editions also include Shamela, Fielding’s hilarious parody of Richardson’s Pamela)

2018

[March 5, 2018]

Film Classics in Berkeley

Two classic literary films will be shown at University Press Bookstore in Berkeley:

Tom Jones (1963; directed by Tony Richardson; screenplay by John Osborne. 125 minutes). This delightful film won four Oscars, including best film and best screenplay, with six nominations for best actors and supporting actors. Kenneth Rexroth had this to say when it first came out: “By and large, pictures that move don’t move me, but Tom Jones is close to the best that the industry can do. It is a landmark in the history of cinema, as they say in the highbrow reviews, which means that it does not insult the intelligence of an adult.” www.bopsecrets.org/rexroth/sf/1964.htm

Sunday, March 11, 6:00 p.m., at UPB (2430 Bancroft in Berkeley).La Princesse de Clèves (1961; directed by Jean Delannoy; screenplay by Jean Cocteau. 100 minutes. French with English subtitles). This intense, tightly knit drama features superlative acting with authentic Renaissance costumes and decor.

Sunday, March 25, 6:00 p.m., at UPB (2430 Bancroft in Berkeley).

Film adaptations of literary classics are usually

disappointing. These two are among the rare

exceptions

that manage to be excellent cinematic works while

conveying the gist of the original works. They are a

supplement to UPB’s ongoing reading series, “Exploring the Classics with Ken Knabb,” but you

can enjoy

the films even if you haven’t read the books. Each

film will be introduced by Ken and followed by open

discussion.

Tristram Shandy reading group

Dear Bay Area Friends,

Beginning April 8, I will be facilitating discussions of Laurence Sterne’s novel Tristram Shandy. Please let me know if you’d like to join us.

Tristram Shandy (1760) is a truly unique work — a zany, endlessly meandering exploration of the vast possibilities of life and literature, and at the same time a wry demonstration of their limitations. Much of the book is presented through stream-of-consciousness (more than a century before Joyce and Woolf) and the characters’ thoughts are full of odd and embarrassing things just like yours and mine are. Yet throughout all the seemingly chaotic narration the characters are being revealed with a whimsical but ultimately compassionate humor. The astonishing narrative innovations are what first strike the reader, but those characters and that good humor are what continue to make this book loved as well as admired.

“Sterne is the most liberated spirit of all time, in comparison with whom all others seem stiff, square, intolerant, and boorishly direct. . . . He, the supplest of authors, communicates something of this suppleness to his readers. Indeed, Sterne unintentionally reverses these roles, and is sometimes as much reader as author; his book resembles a play within a play, an audience observed by another audience. . . . The reader who demands to know exactly what Sterne really thinks of a thing, whether he is making a serious or a laughing face, must be given up for lost: for Sterne knows how to encompass both in a single facial expression, how to knot together profundity and farce.” (Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human)

You can read the complete Nietzsche passage here — https://biblioklept.org/2012/03/22/the-freest-writer-nietzsche-on-laurence-sterne/

And here’s Rexroth’s essay on Tristram Shandy —

www.bopsecrets.org/rexroth/cr/6B.htm#Tristram-Shandy

[May 24, 2018]

Looking ahead with our book group

Dear Fellow Explorers,

I’ve been leading the “Exploring the Classics” group at University Press Books for the past two and a half years. I’ve enjoyed it a lot, and my impression is that most of the other participants have too.

We are now approaching the end of the originally planned series of readings. After Tristram Shandy (3 more meetings) we’ll be doing Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist (4 meetings) and then conclude with some selections from Boswell and Johnson (7 meetings), which will take us to the end of this year.

Bill McClung, our esteemed UPB host, has said he’d like me to continue leading the group in this manner “forever.” That seems a bit excessive, but I am willing and indeed eager to carry on for the next few years.

In fact, I’ve already planned a new series of great novels and poems (and even some songs!) of the 19th century and early 20th century (mostly French and English), which will take approximately two years. Then I envision dropping the exclusively European focus and embarking on a several-year journey through a wider range of classics from diverse periods and cultures around the world.

But before I go into detail about all that, I’d like to hear from you. Are you okay with my continuing to lead the group and choose the readings, as I’ve been doing? Or would you prefer to have different leaders or facilitators, or to do different kinds of readings? Please let me know your thoughts about these issues, or about any problems you may have had with the group, or any suggestions you may have for improving it.

Cheers,

Ken

(I’m sending this message to

the 60+ people who have attended at least three

meetings of the group.)

NOTE:

That announcement/query got a

couple dozen replies, all enthusiastically urging me

to continue just as I had been doing. I’ll quote

just one of them:

“First, I vote that you lead the group for as long as you can and want to do so (which, like Bill, I hope is forever). You are such a good facilitator, and really know the works and talk about them intelligently. Not so many people can do that. You are a natural at it, so please don’t hand it over to someone else. Adding more facilitators will just alter the flow of it all. Changes? Suggestions? I don’t know that you need to change anything. I don’t think improvement is needed. I love this reading group so much! It is so wonderful on many levels: the people are all avid and interested readers, the works are so important and I am learning so much, and the charming setting (surrounded by excellent books) and the good wine and tasty snacks — it all works so perfectly. I always look forward to the book group on alternate Sundays, which is also the perfect frequency for such an endeavor. Thank you so much for all the wonder and knowledge and joy you share! You put so much energy into it, I am always amazed. You are one of the reasons that Berkeley remains an interesting place to be.”

[June 21, 2018]

Nine-Year Plan

Dear UPB Book Group Participants,

Responses to my recent

email query (“Are you okay with my continuing to

lead our

book group and choose the readings?”) were

overwhelmingly and in many cases

enthusiastically in favor. I’m very grateful for

this confidence and appreciation — but

you may not have realized just what you were

getting yourselves into!

Here’s my tentative plan for the next six years (with estimated number of meetings). I’m excited about all of these works, including how they interconnect with each other in multitudinous ways, and I hope you will join us for as many of them as possible.

SERIES 1

(2016-2018):

Cervantes, Don Quixote [12]

Montaigne, Selected Essays [10]

Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantegruel [6]

Bunyan, Pilgrim’s Progress [4]

Swift, Gulliver’s Travels [4]

Madame de Lafayette, The Princesse de Clèves

[4]

Defoe, Moll Flanders [4]

Fielding, Tom Jones [7]

Sterne, Tristram Shandy [7]

Diderot, Jacques the Fatalist and His Master

[4]

Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson

(abridged) + Selected Writings by Johnson [7]

SERIES 2:

2019

Stendhal, The Red and the Black [7]

Balzac, Lost Illusions [7]

Flaubert, Madame Bovary [6]

Blake, Selected Poems [4]

2020

Whitman, Selected Poems [4]

Baudelaire, Selected Poems [4]

Rimbaud, Selected Poems + A Season in Hell

[4]

Other French Poets 1850-1950 [5]

French Songwriters 1820-1980 [5]

2021

D.H. Lawrence, Women in Love [6]

Ford Madox Ford, Parade’s End [11]

Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook [8]

SERIES 3:

2022

The Epic of Gilgamesh [2]

The Mahabharata (abridged) [4]

Herodotus, The Histories [10]

Poems from the Greek Anthology [2]

Sappho, Selected Poems [2]

Apuleius, The Golden Ass [3]

2023

Tao Te Ching + Chuang Tzu [4]

Tu Fu, Selected Poems [4]

Basho, Selected Poems + Narrow Road to the

Interior [4]

Women Poets of China and Japan [3]

Cao Xueqin, The Dream of the Red Chamber

(abridged) [4]

Arabian Nights (selections) [6]

2024

Njal’s Saga [5]

The Kalevala [6]

Paul Radin, African Folktales [3]

Jaime de Angulo, Indian Tales [3]

English and Scottish Folk Ballads [4]

Shakespeare and Robert Burns, Selected Songs [3]

SERIES 4 (2025 and

after):

Continue roaming among various classics

and/or

Explore some more modern works

and/or

Tackle The Tale of Genji (which would

take about a year to do appropriately) . . .

Note: I’ve already

chosen particular translations and/or editions

for most of these

works, but I’m omitting them here so you can get

an overview of the whole selection

without too much clutter. I’ll send out those

details sometime soon, in case you want

to read some of the books ahead of time.

NOTE: As you can see from the above, the Exploring the Classics

group is not run democratically. My proposed program

of readings was indeed democratically accepted by the Proust core group

back in 2015, but I was given carte blanche to organize everything and

work out the details. Three years later, when we had gone through the

series of books I had proposed, I figured that was the end of my

“mandate.” Hence my query to the group participants. Since there was

enthusiastic unanimity in favor of my continuing as before, I have done

so.

There are, of course, many other ways to organize book groups. When a correspondant some time ago asked me How do you run a book group? I replied in part as follows:

There are many different ways. Depends on where and how often you’re meeting, how many people are in it, what topics or genres are being read, what diverse interests or expertises the participants have, how you determine which books will be read, who facilitates and how, etc. There’s an interesting book called Salons: The Joy of Conversation by Jaida Sandra & Jon Spayde that goes into all sorts of group types and group dynamics (book groups being simply one type of “salon” among many others).

One common problem in book groups is that people often disagree about which books to read. One solution (if you’re envisaging longer works) is to vote and go with the majority. Another is to do short works and rotate the choice from person to person. This latter method may provide some balance and variety, but it also risks leading to a lot of so-so works being chosen simply because they just came out and have been favorably reviewed somewhere. Another alternative is for one person who is reasonably qualified to take the initiative and see who coalesces around him or her. This is how my classics group works. I choose the books and I lead the discussions. Those who are interested in the particular books I’ve chosen (or who trust my judgment and are happy to go with whatever I choose) join the group. Others are of course free to join other groups or to form their own groups with different texts and processes. I also take part in two other groups where someone else is in charge in a similar way. . . .

It remains to be seen how your group will fit in with all these possibilities. You’ll have to work out things like what to read and who facilitates and how they do it. The important thing is to encourage active participation by everyone in the discussion — that’s where you really learn things and develop your critical skills, instead of just absorbing information or approved viewpoints. . . .

However it works out, the process is usually interesting and fun! Let me know how it goes.

Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist

Dear Bay Area Friends,

Beginning July 22, I will be facilitating discussions of Diderot’s novel Jacques the Fatalist and His Master.

Denis Diderot (1713-1784), one of the pivotal figures in human history, is most well known for editing the Encyclopédie, but he was an extremely versatile thinker and writer in numerous fields, including fiction. Jacques the Fatalist and His Master is a lively picaresque/philosophical/satirical “novel” in which, in contrast to Don Quixote, the servant is far more intelligent than his master. It has numerous modernistic or even “postmodern” features, partly inspired by Sterne’s Tristram Shandy.

“Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy and Denis Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist are for me the two greatest novelistic works of the eighteenth century, two novels conceived as grand games. They reach heights of playfulness, of lightness, never scaled before or since.” (Milan Kundera)

“This is not a usual novel. Diderot has written Jacques the Fatalist to show what a novel is not, what a novel could be, and, in many ways, to suggest that all that has been called the novel before should be dismissed. . . . Jacques is pregnant with premonitions of modern literary aims. Stream of consciousness, surrealism, flashback, and time manipulation — they’re all here in Diderot, whether or not he was fully aware of the potential of his playful experiment.” (Robert Loy in his Translator’s Introduction)

[July 24, 2018]

Diderot-related topics

Dear Diderotistes,

We will have two more meetings in which we will directly read and discuss Jacques the Fatalist (August 5 and August 19). Then, for our final meeting (September 2) I’d like to open things up in various directions. We can continue to discuss anything about the book, but I think it would also be interesting for any of you who feel like it to read one of Diderot’s other works, or some work or topic related to him or his time, and give us a 5-minute report on it.

Here are some suggestions:

Diderot, Rameau’s Nephew [Diderot’s other major fictional masterpiece, about 100 pages]

Diderot, D’Alembert’s Dream and/or Conversation Between D’Alembert and Diderot [two philosophical dialogues]

Diderot, The Nun [an anti-religion novel]

. . . or any other works by Diderot [he wrote a number of shorter discourses on various topics and a lot of art criticism, and there are various selections of his letters, etc.]

Jean d’Alembert, Preliminary Discourse to the Encyclopédie

Philipp Blom, Enlightening the World: Encyclopédie: The Book That Changed the Course of History [or any other study of the Encyclopédie]

Philip Furbank, Diderot: A Critical Biography [or any other bio or study of Diderot]

Alice Fredman, Diderot and Sterne [I can loan you my copy.]

Josef Weber, Appeal for an English Edition of Diderot’s “Jack the Fatalist” [I’ll soon be sending out a PDF of this lengthy article.]

A. Robert Loy, Diderot’s Determined Fatalist [the first major study of Jacques the Fatalist in English, but very hard to find]

A. Robert Loy, That Infernal Affair [letters between Diderot, Rousseau, d’Alembert, Voltaire, Madame d’Epinay, etc., revealing their multifaceted interrelations, disputes, jealousies, and domestic complications. Reads like a novel, or even a detective story (who is going to break up with whom? who was at fault in this particular dispute?). I can loan you my copy.]

Milan Kundera, Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts

Pierre Beaumarchais, The Marriage of Figaro [the play, not the opera]

Please let me know if you would like to read and report on one of these

works.

[August 30, 2018]

Dear Diderotistes,

A reminder that our fourth and final Jacques the Fatalist meeting will be this Sunday (September 2). This meeting will feature short reports on various Diderot-related topics. So far, the following six reports are planned:

— Marie-Paule will report on Diderot’s Supplement to Bougainville’s Voyage

— Jim will relate Jacques to My Dinner with André.

— Lucia will report on Beaumarchais’s The Marriage of Figaro.

— Bill G. will report on Diderot’s friend Baron D’Holbach and the issues of fatalism/determinism.

— I will report on Diderot’s Rameau’s Nephew

— I will also report on Josef Weber’s Appeal for an English Edition of Diderot’s “Jack the Fatalist” (www.bopsecrets.org/CF/weber-diderot.htm).

Let me know if you’d like to report on any other Diderot-related topic (suggested time 5-10 minutes). But there is no obligation — feel free to simply sit back and listen to the others’ reports and maybe ask them some questions.

P.S. Milan Kundera wrote a play

called Jacques and His Master.

You can read his very interesting

Introduction to it here —

https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/98/05/17/specials/kundera-variation.html

Boswell-Johnson reading group

Interviewer: “What is your desert island book?”

Samuel Beckett: “Boswell’s Life of Johnson.”“Boswell’s Johnson is one of the greatest creations in English Literature, second only to Sherlock Holmes.”

—Terry Bisson (award-winning science fiction writer, who will be joining our discussions)

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) was the dominant literary personality of his era — compiler of the first great English dictionary, editor of Shakespeare, biographer of the English poets, author of poems, essays, and fiction, and “the greatest social talker whose talk has been recorded.”

James Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson (1791) is widely considered one of the greatest biographies ever written, both because of the unique charisma and eccentricities of its subject and because of the innovatively intimate manner of its narration. Much of it consists of Johnson’s conversations, responding to questions by Boswell or skewering others with the witty putdowns that have made him one of the most quoted persons in history.

Beginning September 16, our “Exploring the Classics” group will be reading and discussing an abridged version of Boswell’s book along with selections from Johnson’s own writings. We’ll be using The Portable Johnson and Boswell (Viking Press, ed. Kronenberger). This book is out of print, but you can easily find a cheap used copy here — www.abebooks.com/servlet/SearchResults?sts=t&cm_sp=SearchF-_-home-_-Results&an=&tn=portable+johnson+and+boswell&kn=&isbn

Please let me know if you’d like to join us.

[November 22, 2018]

Boswell-Johnson reports

Our final Boswell/Johnson meeting (December 9) will be devoted to individual reports on other works by Johnson or Boswell or on related topics. So far, we have tentatively lined up:

— Sabrina, reporting on the book Dr. Johnson’s London

— Gerhard, reporting on the book Printing Technology, Letters, and Samuel Johnson

— Alix, reporting on novelist/diarist Fanny Burney

— Lisa, reporting on painter Joshua Reynolds

— Kit, reporting on Johnson’s and Boswell’s accounts of their trip through Scotland

— Ken, reporting on Johnson’s philosophical novel Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia

— Ken, reporting on Boswell’s private journals

Let me know if you would also like to do one. But there is absolutely no obligation — you are quite welcome to simply take it easy and enjoy the others’ reports. As you can see, we’ve already got a pretty full schedule.

Reports should be around 8-10 minutes long. At the 12-minute point a stern warning will be given. At 15 minutes the speaker will be bound and gagged even if he/she is in the middle of a sentence.

Following the December 9 meeting we

will take a holiday break, then resume

on January 6 with Stendhal’s The Red

and the Black.

The Red and the Black

Dear Bay Area Friends,

Beginning January 6, 2019, I will be facilitating discussions of Stendhal’s superlative novel The Red and the Black. We’ll be using the Burton Raffel translation (Modern Library paperback).

“Hardly another man of letters has been as much a man of the world as Stendhal. Napoleon’s commissary officer on the retreat from Moscow; consul in Civita Vecchia, the port of Rome; wit of the salons of the Empire and terror of those of the Restoration; lover of actresses, courtesans, and noblewomen — this is a man to whom words were always instruments of action. He is an adult writing for adults. . . . In its sharp definition, breathless pace, crowded frames, melodrama, The Red and the Black anticipates the methods of the cinema. But its characters are like so many modern people whose disasters are spread on the newspapers: they seem to have seen too many movies. As the novel progresses, their actions acquire an ever-increasing, ever more agonizing ridiculousness. The hero, Julien Sorel, is destroyed by the mean unreality of the world in which his Napoleonic campaigns of sex and ambition are planned. His battles must be fought not with armies, but with the limitless fraud of organized society. The Red and the Black is the first black comedy.” (Rexroth)

2019

Balzac’s Lost Illusions

Dear Bay Area Friends,

Beginning March 17, I will be facilitating discussions of Balzac’s great novel Lost Illusions. . . . We’ll be using the Kathleen Raine translation (Modern Library paperback).

“Balzac is the epic poet of the barbarous age of industrial commercial civilization, what Marx called the period of primitive accumulation. The two authors even have certain emotional and personality traits in common. Both are daemonic writers driven by prophetic fury into rebellion against the human condition. This is overt in Marx but is always there, just below the surface, in Balzac, ready to erupt in caustic analysis of human motivation. . . . Balzac’s daemonic possession distinguishes him from all other novelists. In the twenty years of his productivity he wrote more than any other major writer in history. Very little of it is hasty or slipshod, but it is all driven, and it drives the reader. His narrative method takes possession of you in a way that would not be seen again until the full development of the cinema. A novel by Balzac is an obsession which you are at liberty to adopt for a few hours.” (Rexroth)

[May 22, 2019]

Dear Balzacians,

A reminder that our next and last Lost Illusions meeting will be this Sunday (May 26). For this final meeting we will be going around the table to hear people’s thoughts on anything about Balzac or his book. This procedure has often led to very interesting discussions, sometimes including unexpected views about unexpected topics, so I hope you will show up even if you haven’t been able to do all the reading.